⬤ Billions are flooding into artificial intelligence right now, but here's the thing—we're not seeing the productivity boost in the actual economic data. The numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics tell an interesting story: productivity grew at 2.7% annually between 1947 and 1973, then dropped to 2.1% from 1990 to 2001 (right after PCs became common), and fell even further to around 1.5% between 2007 and 2019.

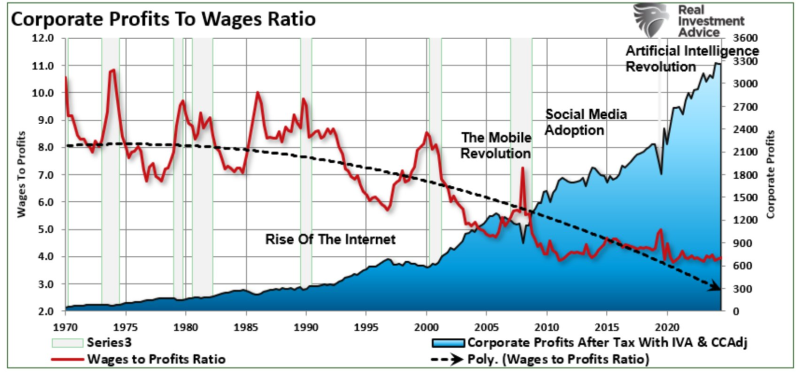

⬤ Economists call this the Solow Paradox—when major tech breakthroughs don't immediately show up in productivity stats. But there's a bigger picture here. Look at what's happened since the 1970s: corporate profits after tax have been climbing steadily, while the ratio of wages to profits has been sliding downward. This happened through the internet boom, the mobile revolution, social media explosion, and now it's continuing with AI.

⬤ AI is definitely making things more efficient in specific areas—some operations are seeing productivity jump from 3% to 6%. But here's what's actually happening with those gains: companies are producing more with the same number of workers, not paying people more or hiring additional staff. That pattern is showing up across different industries adopting AI tools.

⬤ This matters because it shows who's actually benefiting from all this technological progress. The data reveals that profits are capturing more of the gains while compensation isn't keeping pace. Labor's share of GDP has dropped to historic lows. AI might eventually change the game on productivity, but so far it's following the same script we've seen before: output goes up, employment stays flat, and the gap between profits and wages keeps widening.

Usman Salis

Usman Salis

Usman Salis

Usman Salis