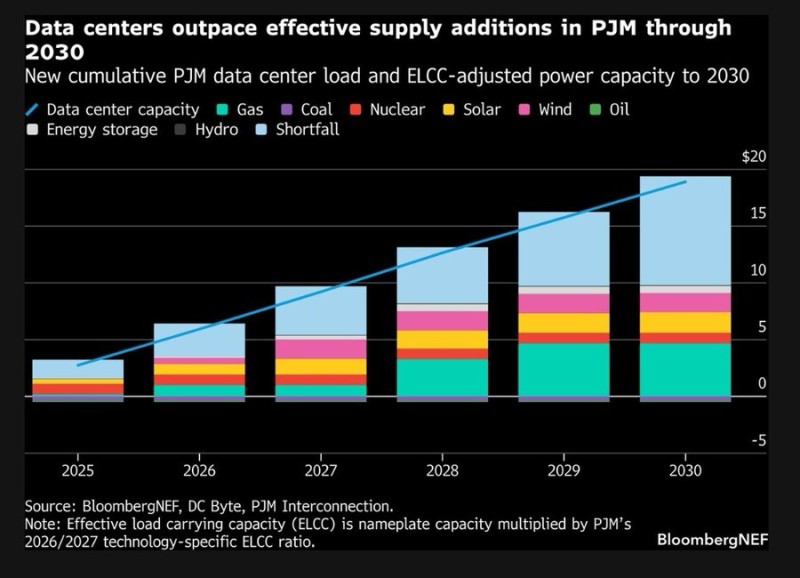

⬤AI infrastructure is eating up power at a pace the US grid wasn't built to handle. Across the PJM Interconnection — the main grid covering a huge chunk of America's data center footprint — demand from computing facilities is on track to outrun new generation capacity every year through 2030. That's measured using effective load carrying capability, a reliability metric that tracks how much power the grid can actually deliver when it's needed most. The growing gap between what AI needs and what the grid can provide is starting to raise serious alarms.

⬤The numbers tell a clear story. Data center demand climbs year after year, while new supply from gas, nuclear, solar, wind, and other sources builds up far too slowly to keep up. Even when you add all those sources together, the total still falls short of projected consumption. The shortfall is sharpest during peak reliability periods — exactly the times when grid stress matters most."Power availability, rather than semiconductor supply alone, is increasingly influencing the pace and geography of AI deployment across the United States."

⬤Tighter supply is already filtering into PJM's capacity auctions, the mechanism used to fund new energy projects. Clearing prices are expected to rise as grid operators scramble to attract new generation investment. Policymakers and federal officials have taken notice, with structural reforms now on the table. The pressure is only likely to grow — broader research points to the same direction, while real-world cracks are already showing up in 16 AI data centers canceled last December due to water and power shortages.

⬤What's unfolding is a fundamental shift in what drives energy markets. Computing infrastructure has quietly become one of the biggest new demand forces in the US power sector. Where AI gets built — and how fast — is no longer just a question of chips and capital. Increasingly, it comes down to whether the grid can keep the lights on.

Alex Dudov

Alex Dudov

Alex Dudov

Alex Dudov